|

A SHARK is a physical marvel. No one has ever seen one asleep, although they may be spied basking in the sun on the surface on a lazy summer day, or resting on the sandy bottom where it is warm and safe. But the golden, restless, ghostly eyes are alert for either enemy or prey. Omnivorous, fated to be ever hungry, relentless, savage, the tiger of the sea never relaxes his vigilance, never abandons his ceaseless search for food which is gulped down his white throat whole. From birth in the depths, a shark has to keep his great lunate tail waving in the sea lanes, his nose keenly alert for odors indicating succulent tidbits or a juicy feast to replenish energy burned up in his perpetually active muscular system.

Sharks are the greatest fish in the world, and the most invulnerable. In every sea, in every clime, they glide silently up brackish river mouths, play in sunlit tropical waters, follow liners across the trackless oceans, migrate by millions up and down the shores of continents, and even live at the 200-fathom mark under the ice fields of Greenland and the Arctic. For 300,000,000 years they have held undisputed sway over the under-sea world, their rows of razor-sharp teeth and armored hides making them invulnerable. They have dominated their subsea domain against even the dangerous rivalry of the fearsome monsters of the past, and now have only themselves to fear. Despite their uncounted numbers through the ages, mankind only recently is beginning to learn something of their habits, their diet, and the uses to which the dead brutes may be put. |

|

There is something indefinably dreadful in the very appearance of these sea monsters, inspiring the utmost terror in the unprotected swimmer. The sight of a shark's ugly green fin slicing in zigzags along the surface, then submerging to become an acute menace, drives terror into the heart of the stoutest seaman. The ogling, chinless face with its ghostly leer, the great cruel mouth framing rows of scimitar-like teeth, the relentless fury with which the fish attacks, his lashing struggles when caught and the ferocity with which he snaps his massive jaws at all within reach, his imperviousness to pain and his invulnerability to injury render him a fearsome antagonist indeed, while his relentless strength engenders nothing but hate for him and his kind among those who must ever guard against his depredations.

Watchfulness, the law of the sea, applies to sharks as well as to all other living creatures. Their span of years-never yet counted by scientists-is dependent upon their own alertness, for, although only another shark can bite a shark, these monstrous fish are patent cannibals, and eat one another as well as everything else in the sea. Let a shark become incapacitated or wounded, and its mates will make short work of it. |

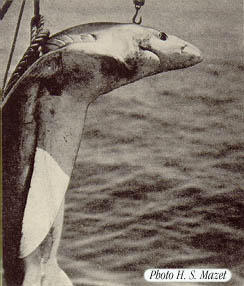

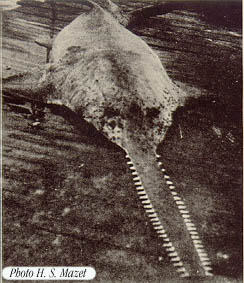

A swimmers nightmare. The upper picture is that of a tiger shark while below, from left to right, we have the sawfish, thresher shark, hammerhead shark, and leopard shark.

|

|

Certain species of these ubiquitous fish produce as many as 50 offspring at a time, born alive in the sea. Others give birth to but a single embryo. The shark shown on p. 1287 (see adjacent photo) carried one, which after removal swam about in a shallow pool just as if it had been born alive in the normal manner. The small mother, although disemboweled, continued alive for a long time and as I held it aloft, twisted and jerked powerfully, in full possession of its faculties. Other species of sharks breed more frequently and give birth to young every few weeks, the babies maturing to be thrust into a cruel world in from 3 to 6 months.

Sharks never lack for razor-sharp teeth, nature having provided a wonderful system of dentition for these pantophagous feeders. Functional teeth stand erect on the edge of the jaws in a single row. As these teeth become worn and lost, the membrane from the inner surface moves over the edge of the jaw, carrying with it fully developed teeth of a new, secondary row. At any given time there are behind the functional row of teeth, rows in reserve of from 5 to 7 in number, lying recumbent one below the other on the inner surface of the jaw, all in reserve being covered by a broad band of membrane that extends up over them from the bases of the jaws.

These are the terrible weapons which have ability to slice into the shagreen-protected hides of other sharks, when they snap out chunks just as you would take a bite out of an apple. |

Sand shark caught at the island of St. John, Virgin Islands. Though disemboweled, the fish is still threshing.

|

|

But even more important to a shark than this is his ability to smell. Two prominent nostrils in the anterior extremity of the head, covered with movable skin flaps, permit him to scent his food in an uncanny fashion from unbelievable distances. Eskimos know that when seal blood is allowed to ooze from a chill bladder placed in an ice hole, the sharks, no matter how distant, will scent it on the sea currents and come hurrying in a horrible rush. Woe to the juicy sea animal which cannot successfully hide from the shark once it has been scented, for the shark will track down its prey like a falcon and with conclusive results.

When a kill was made, on a cruise of the old sperm whaler Daisy of New Bedford, countless sharks would congregate suddenly, drawn to the scene by the blood and juices floating in the sea. They came from every direction, uncannily, menacingly, like hyenas around a dead zebra, assembling so rapidly that the sea would fairly boil with them in short order. The evil brood would file silently by the whale carcass in a sinister, macabre procession. Let one start by attacking the flesh, and instantly the sea was a mass of scrambling sharks as they pushed themselves headlong against the carcass so thick that they overlapped in layers, each trying to bury its teeth in the luckless whale. Many rushed so savagely that in their eagerness they were thrust out of water onto the carcass until a whaleman cut short their murderous careers with a blubber-spade thrust or two.

All giant fish belonging to the shark family are protected by a horny covering of adamantine shagreen, or placoid plates, which provides a resistant protection against attack. In fact this substance is so hard that, when removed, it often wears down emery wheels. Most of it today is removed by chemical solution which eats away the surrounding tissue only, leaving a very fine grade of exceedingly tough and beautiful leather, far stronger than the best cowhide ever tanned. Added to this, the amazing speed of which a shark is capable for short intervals, estimated by natives of many countries at from 35 to 40 miles an hour, results in a truly formidable antagonist among under-sea denizens.

Geologic ages revealed in deposit beds show that sharks have lived in all parts of the world. Yet, strange to say, almost nothing is to be discovered in evidence of sharks through past ages except teeth. The beds of the world's oceans are paved with the teeth of these big fish, sloughed off year after year and dropped into the ocean floor, or deposited as their hosts died.

Since there is no real bone in a shark, only teeth remain undissolved by time and the sea to show that there were giants in those days too. Many which have been found are now fossils, turned to stone by action, ironic reminders of the existence of the sea's roving terror.

It is perhaps fortunate that sharks have so little susceptibility to pain; they are regarded by sailors everywhere as fair game upon which to practice all sorts of barbarisms because of the innate hate bred through centuries among seafaring men and those who go down to the sea in ships.

Many of the small dogfish sharks, caught by fishermen whose nets they ruin, are subjected to a quick, upward thrust of the hand under the protruding snout, breaking the flat nose, whereupon the fish are released. This head projection, the vane of the shark's maneuverability, is irreparably damaged, and the fish, being unable to dive, spends its last hours skittering along the surface until finally it dies and sinks to the bottom or falls prey to its cannibalistic cousins. Kanakas in the Pacific slash the tail fin from sharks, release the catch, and laugh with glee as their savage enemy is reduced to an enfeebled and powerless shadow of its former menace.

A shark, when not wounded in a vital spot, will struggle against capture until it dies from loss of blood or until its mates fall upon it and savagely tear it to pieces. Some sharks have been hooked, shot full of lead from a repeating rifle, then harpooned, hauled on deck and disemboweled, yet have continued alive for a long time, thrashing their tails and snapping their huge jaws in futile rage. A blue shark, horribly mutilated by repeated thrusts from a whaleman's spade, has been seen to return to its prey with unremitting vigor, and to continue snapping until it practically died in the act and sank slowly down into the dark depths of the sea.

Sleeper sharks from Greenland when caught in summer by Eskimos in kayaks are drawn across the skin deck of the boats where their valuable liver is cut out by the hunter. Often, if the native is not alert, the shark will snap its jaws, and occasionally will devour its own liver, before the Eskimo can safely get it to shore, or before the remainder of the fish is cast off, when it will slither to the bottom and be consumed by its fellows.

Many are the tales of the insensibility of these great brutes. A whale shark (Rhineodon typus) which was found swimming haphazardly about a lagoon near Miami, Florida, some years ago, was harpooned several times by a large fishing boat, which thereupon was towed around for 12 hours. The shark was shot more than 50 times with a rifle, without apparent effect. Meanwhile the back of the monster, projecting above the water, was shot at by a shotgun from a distance of 2 feet. The shot bounded back, leaving a dent of some inches in the hide. The gigantic leviathan did not seem to realize what was happening to it. Finally it was beached, and its brain injured. After death, it was dragged ashore, although not without difficulty, for it broke the winch on the marine railway. The specimen weighed 13 1/2 tons, had a hide 4 inches 2 thick, with white lines and spots on it in regular patterns, and two minute eyes which proclaimed it a creature of the depths.

The whale shark, rarest as well as largest of all fishes, is estimated to grow to a length of 70 feet, has a mouth large enough to engulf a man, and possesses 6,000 teeth! But they are all microscopic. This greatest of all gill-breathers is harmless to man, and lives almost entirely on plankton, the minute animalcula of the sea.

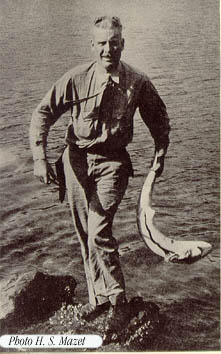

The shark-fishing industry, once firmly entrenched in Australia, is now moribund there purely because of local conditions. Along Florida's coast and in the Bahamas certain ships are now engaged in the trade of furnishing shark hides for tanneries, but speaking generally the industry suffers from lack of capital and inadequate supervision. Hides are shipped to a tannery the meat is eaten or made into fertilizer high in ammonia content, and the fins are sold to the Chinese who make a delectable soup therefrom. Among those who are responsible for the creation of this commendable industry is Captain William E. Young, native of California, who has started and operated sharkfishing stations all over the world from Cape Cod to Australia during the past 35 years or more.

I first met Captain Young 5 years ago, between expeditions, and soon we were busy talking, catching, and writing about his finny prey. Talking about the days when he and his partner, Captain Ernest Schuetz of the Bahamas, used to net the big scavengers along the coast of North America, he said:

We caught about 350 sharks a month right off a beach near Nantucket, Massachusetts, where people were bathing without a thought of the savage fish which wander up and down that coast by the thousands every year, with the schools of menhaden upon which they feed. But of course almost none of the sharks we caught was a dangerous type, although the murderous blue shark once in a while put in his feared appearance. It was on one of these days that I became quite careless. |